Click here to read the previous post, Adjusting to Life in Spain: A “Foreign Film” at Cine Doré

I only wrote “shit” in the title because “International Systems, Symbols and Other Differences Between Spain and the U.S. I Have to Get Used To” is too long. I actually find these differences interesting and not all that hard (after the first week or two) to get used to.

Here are a few “systems” I have to learn – or re-learn, as a Canuck.

Metric

So here’s the thing about early childhood conditioning: It always sticks with you, for better (ability to climb trees in a dress) or worse (post-divorce abandonment fears). When I was growing up, figuring out whether I needed a sweater or sunscreen that day was done via Celsius. (Well, actually I figured it out by sticking my head out the window. But you get the point.)

Then I moved to the States, saw the current day’s temperature – 80 degrees – and yelped, “What the what?? Why aren’t we all on fire?!”

Welcome to Fahrenheit.

In the twenty-four years that I lived in the U.S. I never did instinctively get Fahrenheit. Every single day of those nearly two and half decades I had to do a mathematical calculation to figure out what the temperature was. Thanks to Bob and Doug McKenzie (of SCTV), though, this was math I could easily do in my head.

Source: Toronto Star

From Celsius to Fahrenheit: Double it and add thirty (it’s more fun when you say this in a hoser accent). So if it’s 25°C…

25 x 2 = 50 + 30 = 80

Thus 25°C equals 80°F.

It works in reverse, too, if you’re an American going to, well, pretty much any other country in the world (there are only three countries that still use the imperial system, and two of them that do not begin with the letter “U” are in the process of switching to metric).

So the minute I stepped foot in Spain and saw the temperature, it was like putting on a pair of comfy shoes that fit perfectly. When a thermometer stated that it was 41°C, I knew exactly how much I was going to sweat my fucking ass off.

However, the caveat in my metric to imperial to metric system again is this: Canada wasn’t always a metric country. Well, no country was. Just depends on the year they officially made the switch. France was the first in 1795.

Check out this nifty color-coded map that shows when each country officially switched to the metric system (or, rather, started the process; it’s not like it happens in a day).

Source: Wikipedia

Canada switched from imperial to metric in 1975, but it’s been rather a lax rule ever since and many people still use a mix of both systems.

Source: Angus Reid Institute

So in all my years in Canada, I’ve used Celsius and kilometers, but feet/inches and pounds. I have no idea how tall I am in meters. This is something I will have to re-(ish)-learn here in Spain.

Time and Date

Besides the fact (ok, opinion) that time moves differently here in Spain versus the U.S., I have to get used to two things about the clock.

One – I’m nine hours ahead of most of my family and friends in Los Angeles and Vancouver, and six hours ahead of other friends in Cleveland. That means when coordinating phone or video calls, one person’s more or less just woken up and the other person’s soon(ish) to go to bed. Trying to have a happy hour call means one of us has a drinking problem. On the other hand, because I’m in the future, I can tell my American and Canadian peeps all about the flying cars and colonies on Mars.

Two – In Europe they use the 24-hour clock (in fact, most of the non-English-speaking world does).

Source: World Population Review

So now I’m back to doing quick math on my fingers. “Your appointment is at 16:00.” (Twelve, thirteen, fourteen, fifteen, sixteen….) “Oh, you mean 4:00 pm!”

Plus the date is written in a different order. (And you can keep your argument about which way is better to yourself. All I care about is: Which way do I write it when I’m in a specific country?)

Whereas North Americans would write November 10, 2024, Europeans would write 10 November 2024. Not a big deal when there are words involved. But trying to decipher 10-11-24 is like solving a quadratic equation without knowing which variable to solve for. (And, yes, I had to look that example up.)

Monetary Unit Symbol

I also have to get used to the decimal comma versus the decimal point in monetary units.

For instance, whereas Americans and Canadians would write fifteen hundred dollars as $1,500.00 Europeans write €1.500,00 instead. A small thing, but a double-take moment in the store for sure.

By the way, roughly half the countries in the world use each of these symbols, in case you’re interested.

Dialogue Quotes

And the last international difference I have come across that I’ve had to get used to (super easy, but again, a tiny bit of a head scratcher at first).

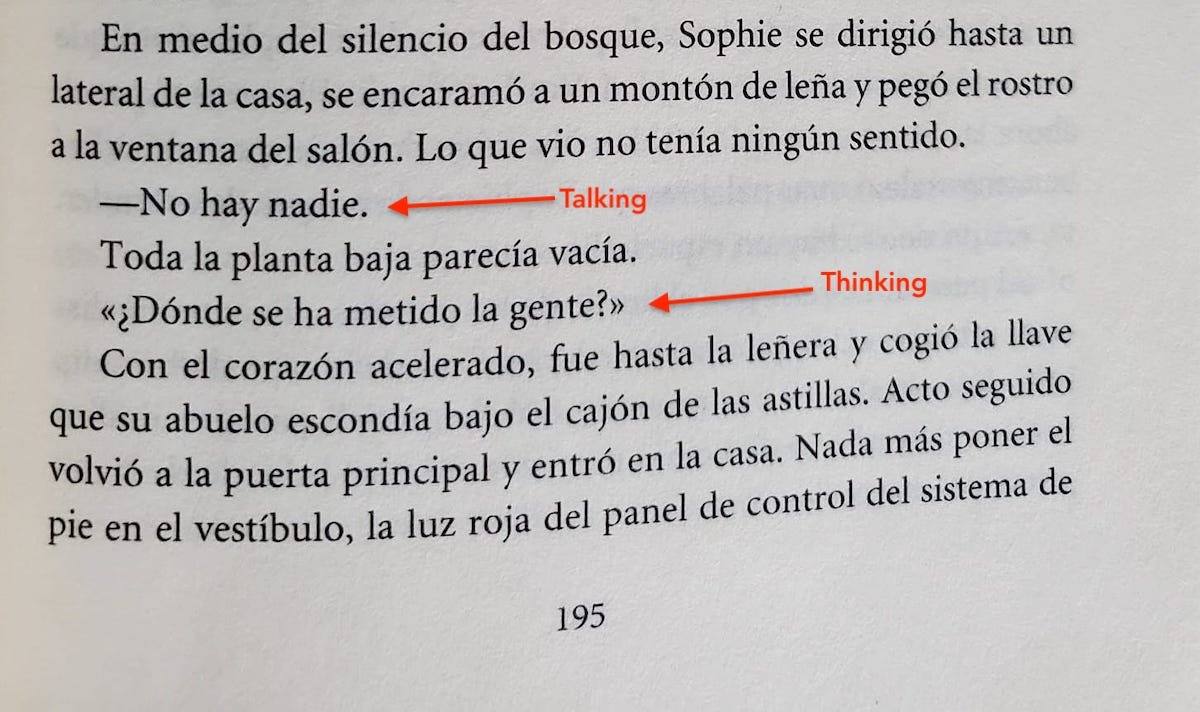

In Spanish books, there are no dialogue quotes, as there are in North American books. Instead, they use em dashes (long hyphens) to indicate when characters are talking, but only at the beginning of the line of dialogue.

And when a character is thinking, they use “guillemets” (aka “angle quotes,” aka “sideways double chevrons,” aka I’m the only one who cares).

Bonus International Shit I Have to Get Used To

Google Translate has a browser extension so you can translate an entire web page with one click. In general it is very helpful. However, if you don’t know Spanish at all, you might just accept the translation at face value.

For example, before purchasing tickets to Grease the Musical, I translated this page just to make sure I knew what I was buying.

The translation turned a fun ‘50s musical into a Victorian-era tale of debauchery and disease. The Gold Whore pricing tier will get you consumption and a hand program.

In case you’re curious:

Butaca oro is not gold whore, it’s gold seats.

Consumición y palomitas is not consumption and popcorn, it’s drinks and popcorn.

Programa de mano is not a hand program (wink, wink), it’s a booklet or playbill.

Click here to read the next post, Adjusting to Life in Spain: Tour of the Prado Museum

Note: All photos taken or created (using DALL-E) by Selena Templeton, unless otherwise noted.

If you enjoyed reading this travel blog, check out some of my other adventures: